Researchers cite growing evidence of highly sophisticated, persistent, long-term campaigns of disinformation—intentionally false or misleading information— organized by both government and non-state actors. Meanwhile, hate speech has become part of the fabric of the burgeoning internet advertising business. In response, many advertisers, leery of the risk to brand reputations, have halted hundreds of millions of dollars in digital ad purchases. Ultimately, many companies profit from the rapid spread of information, no matter the content.

AT THE CENTER OF ALL THIS ARE THE LEADING INTERNET PLATFORMS—INCLUDING FACEBOOK, GOOGLE, YOUTUBE AND TWITTER—THAT ARE VITAL COMPONENTS OF 21ST CENTURY COMMUNICATIONS AND CIVIC DISCOURSE.

In a relatively short span of time these companies have eclipsed traditional, old school media as principal sources of news and information for most of the public and have morphed from technology platforms to brokers of content and truth on a global scale. These companies use algorithms that have an extraordinary impact on how billions of people consume news and information daily.

Open MIC—the Open Media and Information Companies Initiative—is a non-profit organization that works with companies and investors to foster more open and democratic media. We believe the proliferation of misleading and hateful content online presents major challenges not only for civil discourse and society, but also for the leading global internet platforms. This report presents some of the latest thinking regarding the challenges of deceptive content and online hate speech; analysis of the legal, reputational and financial risks to companies; and recommendations for developing greater corporate accountability and transparency on these issues.

There’s a lot at stake. “Getting Facebook to acknowledge that it’s a publisher, not a neutral platform for sharing content, and that its algorithmic decisions have an impact would be a first step towards letting users choose how ideologically isolated or exposed they want to be,” says Ethan Zuckerman, director of the Center for Civic Media at MIT.2

Sir Tim Berners-Lee, the computer science visionary widely credited as having invented the World Wide Web, says: “We must push back against misinformation by encouraging gatekeepers such as Google and Facebook to continue their efforts to combat the problem, while avoiding the creation of any central bodies to decide what is ‘true’ or not. We need more algorithmic transparency to understand how important decisions that affect our lives are being made, and perhaps a set of common principles to be followed.”3

At the same time, many experts caution that simply encouraging companies to play “whack-a-mole” with fabricated internet content does not address the heart of the problem.

“Although a lot of the emphasis in the ‘fake news’ discussion focuses on content that is widely spread and downright insane, much of the most insidious content out there isn’t in your face,” writes danah boyd, president of Data & Society, a research institute. “It’s subtle content that is factually accurate, biased in presentation and framing, and encouraging folks to make dangerous conclusions that are not explicitly spelled out in the content itself. ...That content is far more powerful than content that suggests that UFOs have landed in Arizona.”4

According to boyd, the deeper issue driving the spread of disinformation and hate speech online is an entrenched environment of social and cultural division. Technology platforms, she believes, have an obligation to help bridge that divide, not ignore or exacerbate it. The design imperative “is clear: Develop social, technical, economic, and political structures that allow people to understand, appreciate, and bridge different viewpoints.”

It is beyond the capacity of any company to solve the root causes of what motivates people to spread hateful or even misleading content online. At the same time, major internet platforms play a critical role in building online infrastructure that can help people address—not reinforce—our deep divide.

Among the recommendations discussed in this report:

- To avoid government regulation and/or corporate censorship of information, tech companies should carry out impact assessments on their information policies that are transparent, accountable, and provide an avenue for remedy for those affected by corporate actions.5

- Tech companies should appoint ombudspersons to assess the impact of their content algorithms on the public interest.6

- Tech companies should report at least annually on the impact their policies and practices are having on fake news, disinformation campaigns and hate speech. Reports should include definitions of these terms; metrics; the role of algorithms; the extent to which staff or third-parties evaluate fabricated content claims; and strategies and policies to appropriately manage the issues without negative impact on free speech.7

- There’s considerable debate about what constitutes “fake news” and the role it plays in larger campaigns of disinformation (intentionally false information) and misinformation (unintentionally false information).

- This report uses a definition of “fake news” from Jonathan Zittrain, co-founder of Harvard University’s Berkman Klein Center on Internet & Society, who describes the term based on intent. Fake news, by this definition, is that which is “willfully false,”8 meaning a story “that the person saying or repeating knows to be untrue or is indifferent to whether it is true or false.” Other experts say some fake news combines actual fact with exaggerated or misleading analysis and fabricated headlines. Researchers at NYU and Stanford University suggest that fake news does not include: unintentional reporting mistakes; rumors that do not originate from a particular news article; conspiracy theories; satire that is unlikely to be misconstrued as factual; false statements by politicians; and reports that are slanted or misleading but not outright false.9

- Profit is one motive for creating and disseminating false content. From Macedonia10 to California,11 people have turned fake news stories into lucrative enterprises.

- Fake news has also figured in propaganda campaigns organized by governments or political parties, as well as a variety of other online communities organizing on platforms such as 4chan, Reddit or Twitter; these campaigns have been referred to as the “weaponization of social media.”12 One example is the “small but strategic” role that one study13 found political “bots” to have played in influencing Twitter conversations in the U.K. prior to the referendum on EU membership (otherwise known as Brexit). Currently, U.S. authorities are also investigating Russia’s role in influencing the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

- “Hate speech” is generally defined as news and “information that offends, threatens, or insults groups, based on race, color, religion, national origin, sexual orientation, disability, or other traits.”14 Hate speech can also refer to information or news stories that are intentionally framed to incite hate or anger against a certain group. Such content may or may not include elements of “fake news.”

MEDIA MANIPULATION & THE THREAT TO DEMOCRACY

It’s more than “fake news.” Companies are tangled up in a bigger problem of media manipulation that threatens democracy. Experts agree it’s only getting worse.

Fake news has played a documented role and impacted the political landscape in countries around the globe.15 Pope Francis has condemned it.16 Apple CEO Tim Cook says the proliferation of fake news is “killing people’s minds.”17

BUT OTHERS SAY THE ISSUE IS MUCH BIGGER THAN “FAKE NEWS” AND THAT WHAT WE’RE SEEING ARE INSIDIOUS NEW FORMS OF MEDIA MANIPULATION.

Whatever term we use to describe it, what do we know about the impact of deceptive content online?

“Democracy relies on people being informed about the issues so they can have a debate and make a decision,” says Stephan Lewandowsky, a cognitive scientist at the University of Bristol who studies the spread of disinformation. “Having a large number of people in a society who are misinformed and have their own set of facts is absolutely devastating and extremely difficult to cope with.”18

Conspiracies and media propaganda have long been used to threaten democracy, but today’s online media tools implicate companies in new ways. At the same time, many companies profit from attention-grabbing “clickbait,” incentivizing the presence of information that can rapidly spread, regardless of the content or source of that information.

Researchers at the University of Washington who examined social media activity on Twitter following mass shootings found that “strange clusters” of wild conspiracy talk, when mapped, point to an emerging “alternative media ecosystem” that stands apart from the traditional left-right political axis.19This alternative media ecosystem is focused on anti-globalist themes and is sharply critical of the U.S. and other Western governments and their role around the world.

“THESE FINDINGS ON THE STRUCTURE AND DYNAMICS OF THE ALTERNATIVE MEDIA ECOSYSTEM PROVIDE SOME EVIDENCE OF INTENTIONAL DISINFORMATION TACTICS DESIGNED NOT TO SPREAD A SPECIFIC IDEOLOGY BUT TO UNDERMINE TRUST IN INFORMATION GENERALLY,” THE STUDY FOUND. THE RESEARCHERS SAID THE TACTICS COULD BE “AN EXTENSION OF LENINIST INFORMATION TACTICS,” WHICH AIMED TO SPREAD CONFUSION AND “MUDDLED THINKING” AS A WAY OF CONTROLLING A SOCIETY

A recent survey by Pew Research and Elon University’s Imagining the Internet Center of some 1,500 technology experts, scholars, corporate practitioners and government leaders asked the question: “In the next decade, will public discourse online become more or less shaped by bad actors, harassment, trolls, and an overall tone of griping, distrust, and disgust?”20

Forty-two percent told Pew/Elon they expect “no major change” in the online social climate in the coming decade, while 39 percent said they expect the online future will be even “more shaped” by negative activities. Only 19 percent expected less harassment, trolling and distrust.

Other research shows that misleading content spread on social media platforms is already threatening civic discourse:

- According to Pew, 64 percent of U.S. adults say fabricated news stories cause a great deal of confusion about the basic facts of current issues and events.21 The confusion cuts across political lines: 57 percent of Republicans say completely made-up news causes a great deal of confusion compared to 64 percent of Democrats.

- Fake news was “both widely shared and heavily tilted in favor of Donald Trump” in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, according to a March 2017 NYU/Stanford study. Their database detected 115 pro-Trump fake stories shared on Facebook 30 million times, and 41 pro-Clinton fake stories shared 7.6 million times.22

- Nearly a quarter of web content shared on Twitter by users in the battleground state of Michigan during the final days of last year’s U.S. election campaign was fake news, according to a University of Oxford study.23

- Digital-savvy students from middle school to college display “a dismaying inability to reason about information they see on the Internet” and have “a hard time distinguishing advertisements from news articles or identifying where information came from,” according to a study by the Stanford Graduate School of Education.24 More than 80 percent of middle schoolers believed an ad identified with the words “sponsored content” was a real news story.

HOW COMPANIES ARE RESPONDING TO DECEPTIVE & HATEFUL CONTENT

Companies are making technical changes and drafting policy to articulate how they plan to resist the spread of harmful and deceptive content. However, there are scant publicly-available metrics to evaluate the success of these measures. Meanwhile, companies have yet to address their role as media gatekeepers—and the responsibilities associated with that role.

Google and Facebook can’t by themselves “fix” the spread of propaganda, misinformation or hate speech online.

“The technological and the human-based approaches to controlling inaccurate online speech proposed to date for the most part do not address the underlying social, political or communal causes of hateful or false expression,” writes Ivan Sigal, executive director of Global Voices, a non-profit. “Instead, they seek to restrict behaviors and control effects, and they rely on the good offices of our technology intermediaries for that service.”25

However, Facebook and Google do dominate the online market. In 2016, they controlled an estimated 54 percent of the global digital advertising market, up from 44 percent a year earlier.26 What’s more, they have accounted for virtually all the recent growth in digital ad revenue.27 28

From that powerful position, Facebook and Google greatly shape global online discussion and debate. Both companies have enunciated policies designed to make it more difficult for bad actors to distribute fabricated content for either financial gain or propaganda purposes, as well as to make it easier for users to identify and report false or harmful content. Google, for example, offers AdSense program policies29 and YouTube Community Guidelines30 while Facebook publishes its Community Standards.31 The companies say they have banned fake news sites from using their advertising platforms to generate revenue, but there are no independent metrics to gauge the effectiveness of those policies.

THREE IN FIVE U.S. ADULTS NOW GET NEWS VIA SOCIAL MEDIA. AMONG THOSE, ALMOST TWO-THIRDS GET NEWS ON JUST ONE PLATFORM: FACEBOOK.32

In November 2016, after many months of downplaying the problem, Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg addressed the fake news issue: “The bottom line is: we take misinformation seriously. Our goal is to connect people with the stories they find most meaningful, and we know people want accurate information. We’ve been working on this problem for a long time … We’ve made significant progress, but there is more work to be done.”33

“Issues like false news are bigger than Facebook,” says Adam Mosseri, the Facebook vice president in charge of its News Feed. “They require industry-wide solutions and there are no silver bullets.”34

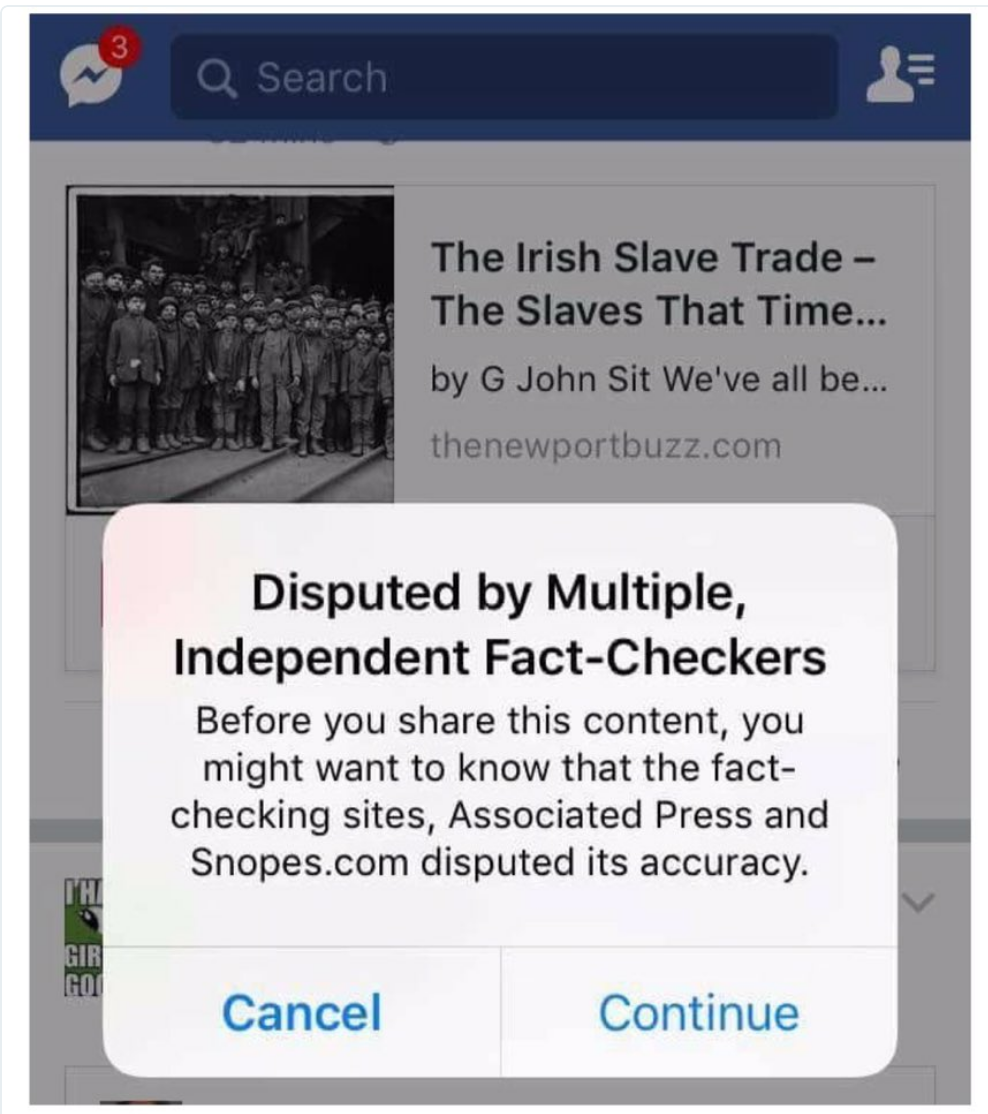

Facebook is now soliciting user input and working with third-party fact-checking organizations.35 While the company initially relied on news organizations to provide fact-checking on a pro bono basis, it recently announced that it is willing to pay third-parties to monitor news feeds; it has reportedly established relationships with third parties such as Politifact, Snopes, Associated Press, AFP, BFMTV, L’Express, Le Monde and Berlin-based non-profit Correctiv.36

If a user reports a story on Facebook to be misleading, and a third-party fact checker then confirms it is inaccurate, the story is flagged as “disputed.”37

A weakness of this approach is that because of the way Facebook’s social networks evolve, disinformation is often circulating among friends with similar ideologies, so fabricated content is less likely to be reported. Another downside is that fact-checking organizations can be targeted as shams by some of the same sources that create or consume fake news in the first place. Says Alison Griswold of Quartz: “One obvious danger of that approach is that Facebook’s users end up reporting stories not along fact-based lines, but on ideological ones...People who don’t trust media outlets to be disinterested observers will recoil at Facebook handing over the ‘arbiter of truth’ role to those sorts of fact-checkers.”38

Robyn Caplan, a Researcher at Data & Society, sees more fundamental problems with Facebook’s approach:

“Facebook will continue to restrict ads on fake news, disrupting the financial incentives for producers. This is something that Facebook and other platforms, like Google, had already committed to doing...For Facebook, this currently means that they will not ‘integrate or display ads in apps or sites containing content that is illegal, misleading, or deceptive.’ However, until Facebook changes its own financial model, which prioritizes content that is easily shared, there is little hope for disrupting the current norms affecting the production of fake news or misleading content. While these policies do inhibit fake news producers from generating money on their own site, Facebook still benefits from the increased traffic and sharing on the News Feed. It’s unclear how Facebook will reduce their own reliance on easily shareable content, which has influenced the spread of fake or misleading news.”

Buzzfeed media editor Craig Silverman, a pioneer in debunking fake news, says a “new, humble Facebook” has emerged in the months since the company was rocked by criticism for the spread of deceptive or false information on its platform during the U.S. election.39

It launched the Facebook Journalism Project in January 2017 to collaborate with news organizations, journalists, publishers and educators “on how we can equip people with the knowledge they need to be informed readers in the digital age.”40 Three months later, Facebook emerged as a leader of a global coalition of tech leaders, academic institutions, nonprofits and funders in a $14 million News Integrity Initiative to “combat declining trust in the news media and advance news literacy.”41

(Non-profit organizations are also mounting efforts to address internet disinformation. In April 2017 a philanthropy started by Pierre Omidyar, the founder of eBay, made a $100 million commitment over three years to address the “global trust deficit.”42)

Google sells advertising in two ways: on AdWords, its program for search-result related ads, and through its AdSense advertising network, which sells ads on more than 2 million third-party websites and millions more YouTube video channels.

In April 2017, Google estimated—for the first time—the quantity of fake news and hate speech results generated on its search engine. It also disclosed new efforts to deal with the problem.43

Ben Gomes, the company’s vice president of engineering, said in a blog post that about 0.25 percent of Google’s daily search inquiries “have been returning offensive or clearly misleading content.” Based on that disclosure and other data, the Washington Post estimated Google users “could be seeing as many as 7.5 million misleading results every day.”44

Google also announced changes to its “Autocomplete” and “Featured Snippets” search features designed to make it easier for users to directly flag content that appears in both features. “These new feedback mechanisms include clearly labeled categories so you can inform us directly if you find sensitive or unhelpful content. We plan to use this feedback to help improve our algorithms,” Gomes said.

Google said it had tweaked its algorithms “to help surface more authoritative pages and demote low-quality content.” It also has issued updated guidelines to its “quality raters,” an army of over 10,000 contractors that the company uses worldwide “to help our algorithms in demoting such low-quality content and help us to make additional improvements over time.”

Tech experts welcomed Google’s announcement but many said it was only a start. “This simply isn’t good enough,” said internet analyst Ben Thompson. “Google is going to be making decisions about who is authoritative and who is not, which is another way of saying that Google is going to be making decisions about what is true and what is not, and that demands more transparency, not less.”45

Separately, Google has also introduced a global Fact Check feature on its search engine which is designed to highlight news and information that has been vetted and show whether it is considered to be true or false.

In 2015, Google helped launch the First Draft Coalition, a non-profit dedicated “to improving practices in the ethical sourcing, verification and reporting of stories that emerge online.” More than 75 news and social media organizations, including Facebook and Twitter, have since joined the coalition, which publishes the First Draft News website.46

For its AdSense network, Google introduced a new “misrepresentative content” policy in November 2016.47 Two months later, the company said it had permanently banned nearly 200 website publishers from the network for violations of policy.48

HATE SPEECH & ADVERTISERS

Advertiser boycotts to avoid ad placement adjacent to hateful content represent a major business risk for companies. One Wall Street firm has estimated that YouTube could see its annual revenue cut by as much as $750 million.

Programmatic advertising — where targeted ad placement is determined by algorithms, and not informed by human judgement — has become a billion-dollar revenue driver for Google.

According to the New York Times, in 2016 Google’s parent company Alphabet made $19.5 billion in net profit, a 23 percent annual jump, almost all generated from Google’s advertising business.49

But advertisers have recently expressed concern about the placement of their ads next to offensive material or hate speech.

A recent article in Buzzfeed — “How YouTube Serves As The Content Engine Of The Internet’s Dark Side” 50

—details some of the problem:

“A YouTube search for the term ‘The Truth About the Holocaust’ returns half a million results. The top 10 are all Holocaust-denying or Holocaust-skeptical...So what responsibility, if any, does YouTube bear for the universe of often conspiratorial, sometimes bigoted, frequently incorrect information that it pays its creators to host, and that is now being filtered up to the most powerful person in the world?”

In reaction to news coverage like this, major U.S. online advertisers including AT&T, Verizon, Johnson & Johnson and GlaxoSmithKline in late March suspended advertising on the AdSense network and YouTube.51

The U.S. controversy followed announced boycotts of Google advertising services in Europe, where ads for a number of U.K. government departments, national broadcasters and consumer brands (Argos, L’Oréal) were placed next to YouTube videos of American white nationalists, among others.52 Havas, a firm that spends £175m annually on digital advertising on behalf of clients in the U.K., pulled all its advertising spending from Google platforms.

Google’s chief business officer, Philipp Schindler, recently told journalist Kara Swisher that the ad placement problem is overblown. “It has always been a small problem,” he said, with “very, very, very small numbers” of ads running next to videos that weren’t “brand safe.” It is just that “over the last few weeks, someone has decided to put a bit more of a spotlight on the problem,” he added.53

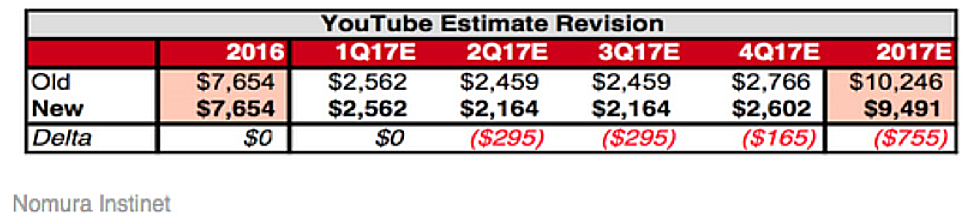

Nonetheless, analysts at Nomura Instinet recently predicted that Google stands to lose up to $750 million—a 7.5% reduction in annual revenue from YouTube—as a result of advertisers pulling content.54

The tech publication recode recently noted that Alphabet has cited programmatic advertising as a major revenue driver in at least its last four earnings calls, mentioning it in that context at least 17 times during that period. “To the extent that the programmatic method of buying is a major source of the content problem at YouTube specifically and Google broadly, that’s particularly problematic for its financial picture going forward,” recode said. 55

Hate speech presents particular risk to Facebook and Google in international markets. In the U.S., laws protecting speech are very broad—and content posted on platforms is not legally the responsibility of the platforms. But in Europe, speech is more closely regulated. In Germany, inciting hatred against particular demographics is illegal on the grounds that it violates human dignity. 56

In April 2017, Germany’s cabinet approved a plan to fine social networks up to 50 million euros ($53 million) if they fail to remove hateful postings quickly, prompting concerns the law could limit free expression. “There should be just as little tolerance for criminal rabble rousing on social networks as on the street,” Justice Minister Heiko Maas said, adding that he would seek to push for similar rules at a European level.57

Maas’s call for new rules on hate speech have drawn severe criticism by multiple civil society organizations.56 Emma Llansó, Director of the Freedom of Expression Project at the Center for Democracy & Technology, says the German proposal would “would create massive incentives for companies to censor a broad range of speech.”59

DRIVING WEB TRAFFIC: THE ROLE OF ‘BOTS’

Malicious “bots” are part of the growing media manipulation ecosystem that contribute to the spread of false content while also threatening companies’ business models.

There is now well-established evidence that companies are being “gamed” by organizations and individuals that fraudulently drive traffic using malicious “bots” (web robots) and “bot nets” (robot networks).

ONE RECENT STUDY FOUND THAT 9 TO 15 PERCENT OF TWITTER’S ACTIVE MONTHLY USERS ARE BOTS.60USING TWITTER’S MOST RECENT FIGURE OF 319 MILLION ACTIVE MONTHLY USERS, THAT WOULD SUGGEST 28.7 MILLION TO 47.9 MILLION BOTS ON TWITTER.

Mark S. Pritchard, CEO of Procter & Gamble, one of the world’s largest advertisers, when asked about digital advertising, told the New York Times, “The entire murky, nontransparent and in some cases fraudulent supply chain is the problem.” Pritchard wondered whether an ad was even “showing up in a place where people are actually viewing it? So, is it a bot or is it a person?”61

Clinton Watts, a former FBI agent, recently described for the U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee massive bot-driven campaigns by Russian hackers, designed to influence American opinion. “What they do is they create automated technology, commonly referred to as bots, to create what look like armies of Americans,” he told the Washington Post. “They can make your biography look like you’re a supporter of one candidate or another, and then they’ll push a series of manipulated truths or fake stories through those accounts.”62

Indeed, the advertising industry’s own data confirms the problem. The World Federation of Advertisers, whose members include McDonald’s, Visa and Unilever, estimated in 2016 that 10 to 30 per cent of online advertising slots are never seen by consumers because of fraud, and forecasts that marketers could lose as much as $50 billion a year by 2025 unless they take radical action. “At that scale,” the Financial Times observed, “the fraud would rank as one of the biggest sources of funds for criminal networks, even approaching the size of the market for some illegal drugs.”63

The advertising industry overall lost upwards of $7.2 billion globally to bots in 2016, according to the ANA. By comparison, according to Pew, all U.S. digital advertising in 2015 totaled $59.6 billion.64

WHAT’S AT STAKE FOR COMPANIES & INVESTORS?

Fake news, disinformation and hate speech present the leading online tech companies and their investors with significant financial, legal and reputational risk.

Hate speech poses potentially material financial risk to companies. Case in point: Alphabet’s Google and its YouTube business.

As noted earlier, Nomura Instinet recently reported that Google stands to lose up to $750 million in annual revenue as a result of clients pulling their ads from YouTube sites.65 One analyst has reportedly downgraded Alphabet stock from “buy” to “hold” because of the controversy.66 And YouTube is not the only platform that stands to lose. According to Nomura, the revenue decline could represent a larger, longer-term trend as advertisers seek to avoid reputationally damaging content on platforms that depend on content generated by the users, such as Twitter, Snapchat, Facebook, Instagram and others.

Without appropriate policies and practices to monitor content, new user applications are dramatically increasing risk.

The 2016 introduction of a Facebook Live video function has led to social media broadcasts of a number of violent criminal acts,67 including a murder in Cleveland.68 Washington Post media columnist Margaret Sullivan has noted that “Facebook still hasn’t come to terms with what it really is—a media company where people get their news. ...But there are, of course, business reasons not to accept that (role). As soon as Facebook acknowledges that it is a publisher and not a platform, it may open itself up to lawsuits that could cut into profits fast.”69

Other experts note that the company has just introduced a Facebook Spaces virtual reality function, a technology that could open the door to new potential risks.70 At its 2017 annual developer conference, Facebook also disclosed that it is working on technology to allow people to control computers directly with their brains71 and to pick up audio waves through their skin.72

Fake news and disinformation campaigns are likely to seek out new targets, including major global brands. These threats could present potential liability for the internet companies.

The consulting firm Booz Allen Hamilton recently warned its clients, “Public corporations, in particular, should be ready for an increased use of disinformation against them to harm their brands. Boards must understand that fake news and disinformation extend the definition of ‘cyber threat’ from a direct attack against a company to an indirect attack via information warfare.”73

Failure to demonstrate compliance with existing regulations could lead to more regulation.

Calls by German authorities for new rules to combat hate speech could be replicated in other countries, especially in the EU, if companies don’t demonstrate progress in dealing with the problem. For example, current EU rules require online platforms to delete or block “obviously illegal” content within 24 hours after it has been flagged, and other illegal content within seven days. One recent study found that Twitter and Facebook deleted only 1 percent and 39 percent, respectively, of content flagged as illegal by their users. (Google’s YouTube deleted 90 percent of flagged illegal content.)74

Without sufficient transparency regarding policies and practices, tech companies could face intense consumer criticism for excluding some content while refusing to discuss the workings of the algorithms that drive their search engines and news feeds.

As noted earlier, YouTube has implemented new processes designed to keep ads from major advertisers from appearing on sites with hate speech. The New York Times has criticized YouTube’s “unfeeling, opaque and shifting algorithms,” noting that “YouTube’s process for mechanically pulling ads from videos is particularly concerning, because it takes aim at whole topics of conversation that could be perceived as potentially offensive to advertisers, and because it so often misfires. It risks suppressing political commentary and jokes. It puts the wild, independent internet in danger of becoming more boring than TV.”75

Vivek Wadhwa, a Distinguished Fellow and professor at Carnegie Mellon University, says increased transparency “does not mean having to publish proprietary software code, but rather giving users an explanation of how the content they view is selected. Facebook can explain whether content is chosen because of location, number of common friends, or similarity in posts. Google can tell us what factors lead to the results we see in a search and provide a method to change their order.”76

DECIDING WHAT CAN’T BE SAID

Companies must uphold principles of freedom of expression.

One of the biggest dangers of current proscriptions that seek to define and somehow block internet disinformation and hate speech is that they will work against freedom of expression.

Ivan Sigal of Global Voices says that in discussions of fake news, “many of the proposed fixes are deeply problematic because they advocate overly broad and vague restrictions on expression. Solutions that would limit suspected ‘fake’ expression or strongly encourage private intermediaries to restrict some kinds of speech and prioritize or ‘whitelist’ others are particularly troubling.” 77

Rebecca MacKinnon, director of the Ranking Digital Rights project at the New America Foundation, told the Pew/Elon researchers she was “very concerned about the future of free speech given current trends. The demands for governments and companies to censor and monitor internet users are coming from an increasingly diverse set of actors with very legitimate concerns about safety and security, as well as concerns about whether civil discourse is becoming so poisoned as to make rational governance based on actual facts impossible. I’m increasingly inclined to think that the solutions, if they ever come about, will be human/social/political/cultural and not technical.”78

David Kaye, the United Nations (UN) Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Opinion and Expression, joined with a number of non-profits in March 2017 to issue a joint declaration on freedom of expression and fake news, disinformation and propaganda.79 The declaration stressed:

“...that the human right to impart information and ideas is not limited to ‘correct’ statements, that the right also protects information and ideas that may shock, offend and disturb, and that prohibitions on disinformation may violate international human rights standards, while, at the same time, this does not justify the dissemination of knowingly or recklessly false statements by official or State actors.

THE PROFIT MOTIVE VS. THE COMMONS

Despite public commitments to limit offensive content and promote free speech, companies have yet to acknowledge how they profit from the spread of that same content. As the business risks of hate speech and disinformation become more clear, this profit motive presents a fundamental tension.

Leading companies are being forced to confront a major shift in their role in the digital ecosystem – where they were once technology platforms, they have steadily become brokers of content and truth.

When asked to comment on the problem Google has encountered—i.e., the tension between the company’s financial dependence on advertising and the fact that algorithms may place ads near hate speech and objectionable content—Sir Martin Sorrell, chief executive of the world’s largest marketing services group, WPP, said: “Google, Facebook and others are media companies and have the same responsibilities as any other media company. They cannot masquerade as technology companies, particularly when they place advertisements.”80

How will companies address the fundamental tension between an existing business model that relies on attention-grabbing content and the need to take responsibility for content that could promote harm?

The Pew/Elon survey—conducted prior to the 2016 elections—reported that “many” of those surveyed felt the “business model of social media platforms is driven by advertising revenues generated by engaged platform users. The more raucous and incendiary the material, at times, the more income a site generates. The more contentious a political conflict is, the more likely it is to be an attention getter.”

The algorithms “tend ‘to reward that which keeps us agitated,’” respondents told the researchers, who lamented the decline of traditional news organizations employing “fairly objective and well-trained (if not well-paid)” reporters who shaped social and political discourse, now “replaced by creators of clickbait headlines read and shared by short-attention-span social sharers.”

Frank Pasquale, professor of law at the University of Maryland and author of “Black Box Society,” commented, “The major internet platforms are driven by a profit motive. Very often, hate, anxiety and anger drive participation with the platform. Whatever behavior increases ad revenue will not only be permitted, but encouraged, excepting of course some egregious cases.”

Andrew Nachison, founder at We Media, a digital producer and consultancy, said, “Facebook adjusts its algorithm to provide a kind of quality—relevance for individuals. But that’s really a ruse to optimize for quantity. The more we come back, the more money they make off of ads and data about us. So the shouting match goes on.”

David Clark, a senior research scientist at MIT and member of the Internet Hall of Fame, sees little incentive for social media platforms to improve: “The application space on the internet today is shaped by large commercial actors, and their goals are profit-seeking, not the creation of a better commons. I do not see tools for public discourse being good ‘money makers,’ so we are coming to a fork in the road–either a new class of actor emerges with a different set of motivations, one that is prepared to build and sustain a new generation of tools, or I fear the overall character of discourse will decline.”

RECOMMENDATIONS

To address the many risks associated with issues of disinformation and hate speech, companies should implement stronger transparency and reporting practices; implement impact assessments on policies affecting content; and establish clear board-level governance on these issues.

While companies can’t solve the underlying problems, they can and should do much more than they are currently attempting.

Some of these challenging issues have already been discussed in the context of terrorist or extremist content on the internet.

In 2015, investors joined companies, government officials, academics and civil society participants in a policy dialogue on extremist content hosted by the Global Network Initiative (GNI). GNI compiled a set of recommendations81 for companies to manage government requests to restrict or remove extremist content from their platforms while also maintaining free speech. In addition to aligning their policies with international human rights standards around freedom of expression, GNI recommended that companies be transparent with users and the public about government requests regarding extremist content. In addition, GNI recommended that “ICT companies should provide mechanisms for remedy that allow people who believe their account has been suspended erroneously as a result of these referrals to seek reinstatement of their account.”

In December 2016, the Center for Democracy and Technology (CDT) outlined preliminary recommendations to avoid the “worst risks” to users’ freedom of expression posed by a shared tech industry database of terrorist content on the internet.82 While CDT strongly opposed the shared industry database, it offered recommendations which might suggest an initial roadmap for companies seeking to implement policies to deal with fake news, misinformation and hate speech. For example, CDT suggested that among a number of steps, participating companies:

- Be required to allow users to appeal when content is mistakenly removed;

- Commit to regular reporting, including the nature and type of material removed and what influenced the company to remove it;

- Allow independent third-party assessment, on a periodic basis, of the material that is registered within a database.

Current controversy regarding the role of internet companies in dealing with misinformation and hate speech shouldn’t come as a surprise. Rebecca MacKinnon recently told the Guardian, “It’s kind of weird right now, because people are finally saying, ‘Gee, Facebook and Google really have a lot of power’ like it’s this big revelation.”

MACKINNON SAYS MOST PEOPLE CONSIDER THE INTERNET TO BE LIKE “THE AIR THAT WE BREATHE AND THE WATER THAT WE DRINK...BUT THIS IS NOT A NATURAL LANDSCAPE. PROGRAMMERS AND EXECUTIVES AND EDITORS AND DESIGNERS, THEY MAKE THIS LANDSCAPE. THEY ARE HUMAN BEINGS AND THEY ALL MAKE CHOICES.”83

For that reason, and to avoid government regulation, she too advocates that tech companies commit to implement policies that are transparent, accountable and provide “an avenue for remedy” for users affected by an internet company’s decisions.84

Further, MacKinnon says tech companies should adopt an “impact assessment model” for evaluating information policy solutions for the private and public sectors. Impact assessments, according to MacKinnon, “could provide us with a more stable foundation for addressing an even more complicated and confusing layer of questions about information manipulation, hate speech, demagoguery, propaganda and media business models without reaching desperately for drastic measures (like holding platforms liable for users’ speech or reviving criminal libel laws) that will ultimately make the global information environment even less free and open.”85

Another recommendation from experts is that internet companies hire and empower “ombudsmen” — something traditional media companies have done for many years — to serve as advocates for readers and viewers. In the context of digital platforms, Courtney C. Radsch, Advocacy Director of the Committee to Protect Journalists, suggests that an “algorithmic ombudsperson” could assess the policies of private tech companies and the assumptions on which algorithms are based to ascertain the impact on the public interest.” 86

“We need new systems that can help generate trust in these platforms and ensure that they are contributing to the common good,” writes Daniel O’Maley of the Center for International Media Assistance, who also advocates for algorithm ombudspersons.

“OPENING UP THE ‘BLACK BOX’ OF ALGORITHMS JUST A LITTLE WOULD GO A LONG WAY IN HOLDING SOCIAL MEDIA PLATFORMS ACCOUNTABLE IN OUR INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM,” SAID O’MALEY.87

Investors have also taken note and are asking tech companies to report on how they are handling the challenges presented by various forms of objectionable content. Arjuna Capital, an investment management firm, has submitted shareholder proposals to Alphabet and Facebook for consideration at the companies’ 2017 annual meetings.88 The proposals ask Alphabet and Facebook to issue reports “regarding the impact of current fake news flows and management systems on the democratic process, free speech, and a cohesive society, as well as reputational and operational risks from potential public policy developments.”

LOOKING AHEAD

Technological solutions could help to thwart the spread of disinformation and hate speech on the internet. Pew/Elon, for example, reported that some respondents to its survey felt “things will get better because technical and human solutions will arise as the online world splinters into segmented, controlled social zones with the help of artificial intelligence (AI).”

However, according to Pew/Elon, even artificial intelligence will create issues around what content is being filtered out and what values are embedded in algorithms. In addition, tech experts “expect the already-existing continuous arms race dynamic will expand, as some people create and apply new measures to ride herd over online discourse while others constantly endeavor to thwart them.”

Whatever course technology takes, it’s clear that the internet and technology companies that drive the 21st century’s social media platforms and search engines need to demonstrate leadership that is substantive and long-term. At the outset of this report, we noted that at birth, the leading internet companies were simply technology platforms; over the years, they have grown into brokers of content and truth on a global scale. It is time they acknowledged and accepted that role and responsibility.

“It has taken all of us to build the web we have,” says Sir Tim Berners-Lee, “and now it is up to all of us to build the web we want – for everyone.”89